Clinical studies and experiments on elite athletes have shown strong correlations between Heart Rate Variability (HRV) and accumulated (training) stress. Currently, companies like HRV4Training and EliteHRV are marketing apps that help you collect HRV data and use them to optimize your training. Also FirstBeat is a known player in this field, promising personalized guidance on training load and recovery, using heart rate variability. In this blog post I am focusing on using HRV to optimize training for “casual” (Masters, age group) athletes in practice.

A casual athlete is an athlete who trains and competes as a hobby. He or she may invest a lot of time training, but this is on top of family, social and work responsibilities, and the training volume and intensity is significantly lower than for elite athletes. The question I am trying to answer is whether HRV measurements provide a meaningful addition to other training information and whether it is possible to (further) optimize training using HRV data. To optimize training, in this personal case, means to achieve better performances and a faster performance improvement for the same training volume.

What is HRV and why is it important?

This section gives you a quick introduction on HRV and why it is important. I have taken the liberty to reproduce the pictures from an excellent presentation by FirstBeat.

Everybody is familiar with heart rate, measured in beats per minute, and how it is applied in training. What is less known is your heart doesn’t beat with the regularity of a metronome. From beat to beat there are slight variations, as shown in the picture. Your heart rate is a measure of the average number of beats per minute. The Heart Rate Variation measures the spread of beat-to-beat intervals (in ms). There are various ways to express HRV. In this article we focus on RMSSD, which is the root mean square standard deviation of beat-to-beat intervals. It is one of several ways to measure the spread of beat-to-beat intervals.

When you work harder, your heart rate increases. Your heart rate is also influenced by other factors like humidity, stress, coffee, drugs, etc.

Another frequent use of heart rate is to measure the resting heart rate (typically measured immediately after waking up) and to monitor it for trends. The idea is that when you are fatigued or about to get ill, the resting heart rate goes up above your normal baseline.

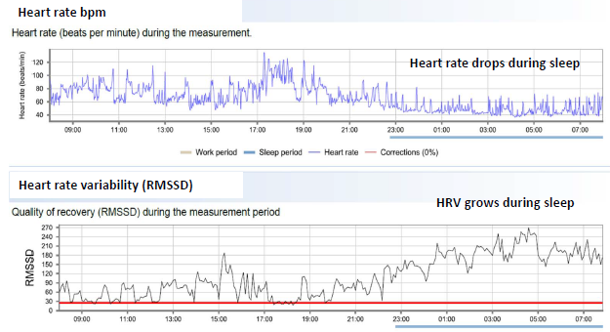

The chart above shows that the heart rate dropping and HRV increasing during sleep (i.e. when you are recovering from the stress of training and the working day). It is generally accepted that an increased HRV indicates that a person is well rested.

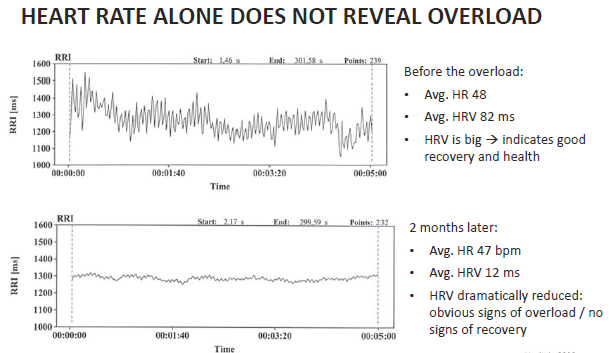

Interesting enough, resting heart rate alone is not always able to signal training overload, stress or the onset of illness. In the chart above you can see that the resting heart rate is around the same value, but Heart Rate Variability is dramatically altered as a result of training overload. So, that seems to indicate that it is smart to monitor HRV, reduce training volume when the values increase (too much) and thus prevent overload and a plateauing performance. This is exactly how HRV is used by elite athletes.

In the past few months I have done a few experiments on myself (and two volunteers) to assess whether such an approach could also work for casual athletes, using low-cost commercially available devices. We looked at whether we could produce meaningful, actionable results in a way that is practical, i.e. does not force you to alter your lifestyle completely.

What are HRV data supposed to represent?

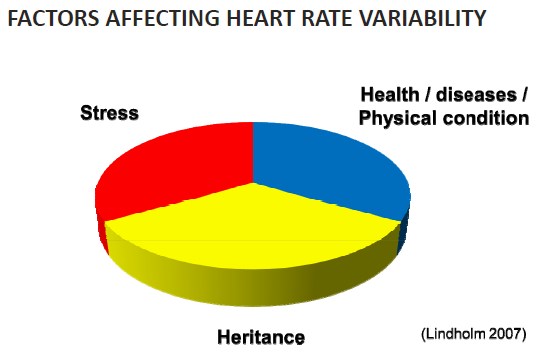

As said above, HRV data are influenced by stress and training overload. The absolute value of the HRV data are determined by stress, physical condition and by heritance.

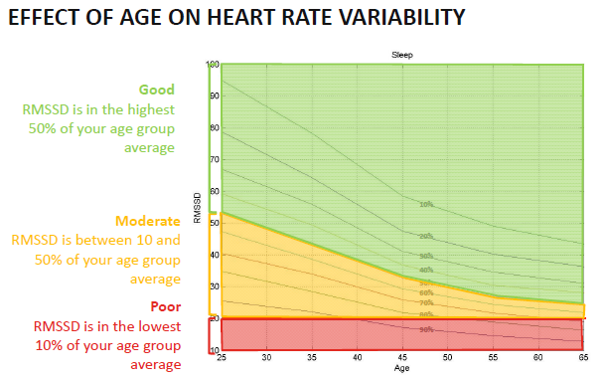

Examples of stress are, among others, fatigue, overload, burnout, lack of sleep, illness, work stress, medications, alcohol and other things. The values of HRV varies across the population and shows a downward trend with age. The chart below gives an indication of the spread of the values.

So, one of the things one could in theory look at is the absolute value of RMSSD and try to correlate that to health and stress. It is important though to establish a baseline because of the genetic factor.

Another important thing to note is that HRV is reduced immediately after heavy endurance exercise. But when you are not overtrained, ill, or stressed, that value should recover quickly.

The first experiments

To get started I obtained a Scosche Rhythm 24 heart rate and HRV measuring device. To record the measurements, I used the HRV logger app by the developer of HRV4Training. I preferred this app over HRV4Training or EliteHRV itself because I was interested in getting the raw measurements (RMSSD, PNN50 and others) as opposed to a general recovery score that the training apps give.

With that set-up I set out with the quite ambitious plan to measure three times per day for 20 minutes, for two weeks time. The time period coincided with a business trip from Europe to India, including long hours, time zone shift, etc.

Unfortunately, this didn’t work out as expected. Even though I could wear the Scosche sensor 24 hours, it was difficult to remember to do the measurements. Also, I didn’t have time for any exercise at all. The trip was just too busy. Finally, when I analyzed all the data it was difficult to see any trends. The only thing that I learned was that I am in the top 10% for my age in terms of average RMSSD score (during that trip).

Even though I didn’t collect much data, an important learning point was how difficult it was (for me) to build the HRV measuring into my daily routine.

Improved Measurements

After the first set of measurements, I decided on a slightly different setup. I would measure only once per day, at 9:30 during a coffee break in the office (coffee allowed only after measuring) and I invited two colleagues to join. The idea was to try and measure for a month and then analyze the data. The Scosche remained in the office so if one of us went on a business trip or vacation, there was no measurement. Also, there were no measurements on the weekend. This represents a more typical usage pattern for the casual athlete, who is too busy to do a measurement immediately after waking up (or may forget), and has to find another daily moment to collect HRV data.

Another important point to make is that, in contrast with elite athletes who have 2 or 3 sessions a day, casual athletes have one or zero sessions, and they may be executed in the morning, afternoon or evening. So the time since the last effort varies from HRV measurement to measurement.

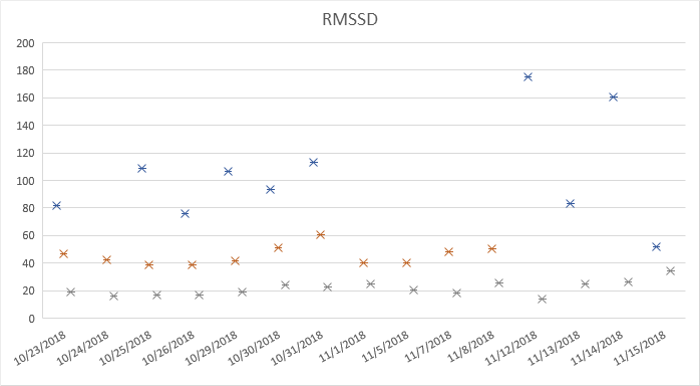

There were three participants in this study:

- A 46 year old male doing above average exercise volumes and getting on average enough sleep

- A 30 year old female doing no structural training, healthy lifestyle, getting enough sleep on average

- A 40 year old male with some overweight and small kids, recovering from illness and getting only about 5 hours of sleep per night on average

While my RMSSD values were above 80, those of my female colleague were between 40 and 60, and my male colleague was improving from below 20 to above 30 during the experiment. He was recovering from illness. In fact, looking at his RMSSD values made him think about how well he was recovering, and he started to take medicine and switch to a healthier lifestyle to improve his situation.

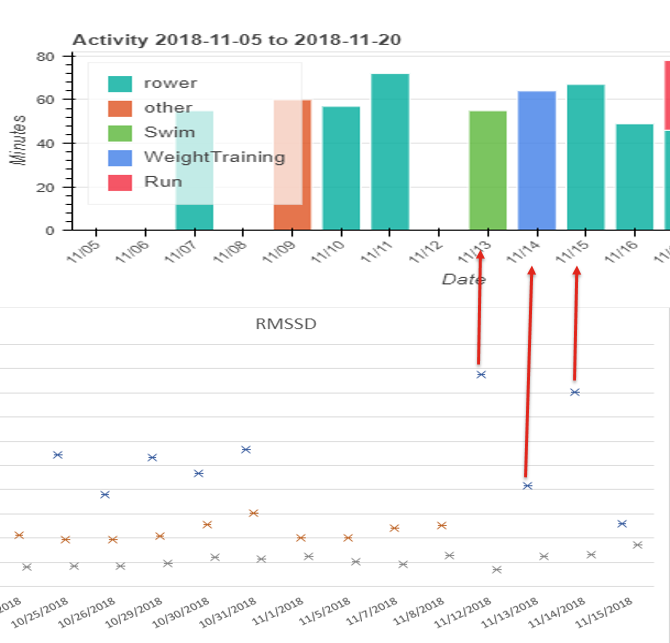

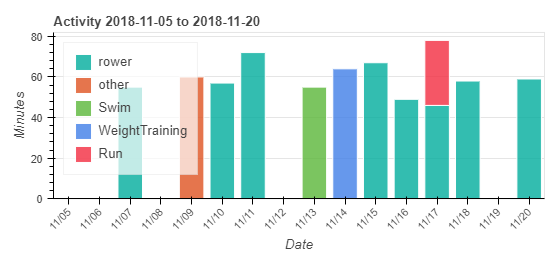

Now on to my data. There are some big jumps there. Do they indicate something related to my trainings? Here is a quick look at my training regimen for part of the period.

The outlier data points are on 11/13 and 11/14.

The outlier data points are on 11/13 and 11/14.

On November 12 I had a rest day because of back issues. That was also the reason why I chose a gentle one hour swim as my morning activity for November 13. Even though the measurement was after the swim, the RMSSD value was high. On November 15 I worked out in the evening, and my measurement was before the workout. The preceding workout was a weights session on November 14. So there wasn’t a lot of endurance stress. Still not sure though why the value was low on November 14.

Another observation was that when we calculated RMSSD per minute for the 5 minute measurements, there were big differences in the value. An average of 50 over the five minutes could be on one day 50 for the entire 5 minutes, and on another day it would be 2 minutes at 20 followed by 3 minutes at 70. That triggers the question whether HRV apps based on measuring only 60 seconds are useful.

Discussion and Conclusions

In the experiment with the three participants, we did see HRV values corresponding to the lifestyle of the participants. Looking at the trends over the month, there seems to be some correlation between Participant 3’s improving health and the HRV values he achieved.

For participant 1, the Masters rower, the values were in the top 10% for his age group, and one may be able to explain the jumps in the data from the training load, but I am not fully convinced here.

We also found it difficult in practice to get the data in regularly. Especially when realizing that 1 minute measurements are probably too short.

Further, we think that a month may be short to establish a baseline. Given the spread in the data obtained in real life conditions, it looks more like two full months are needed.

Because of the jumps in the values, it is difficult to see a trend, unless one works with a moving average. But doesn’t that mean that it takes a week or two to discover that you are in danger of overloading? I wonder if there aren’t easier, lower tech, ways to get warning signals earlier. For example by noting the number of hours slept and completing that with a picture of training load (hours, TRIMP, rScore as measured on rowsandall.com, TSS as measured on TrainingPeaks or the Fatigue measure used on Strava Elevate.

In conclusion, I see little added value to HRV measurements and I think there are easier ways to detect fatigue, illness and training overload.

I may still continue to measure myself to look at longer term effects, but I am not ready to recommend HRV measurements to casual athletes as a tool to make your training smarter.

Note

All participants in the study have agreed to share the data anonymously. The experiments are not meant to be a scientific study of correlations, but merely an attempt to see how HRV could work in practice.