Book: Endure. Mind, body and the curiously elastic limits of human performance

Author: Alex Hutchinson

[amazon_link asins=’0062499866′ template=’ProductAd’ store=’rowingdata-20′ marketplace=’US’ link_id=’2e13efc8-1f85-11e8-b132-3d6e470300c3′]

Training Animal vs Racing Beast

A long time ago, I rowed a single at Orca, a student rowing club in Utrecht, the Netherlands. My good friend Arjan was my sparring partner of those days. We had the same coach, followed the same training plan, were friends off the water (and we are still friends) and fierce competitors during training sessions, always trying to do that next interval slightly faster than the other.

We couldn’t row side by side on the narrow Merwedekanaal, but we closely monitored the gap between our singles, and we rowed timed pieces on “the straight kilometer”. Often, I was faster.

But when we took our singles to the Bosbaan in Amsterdam to participate in 2k races, Arjan was about 20 seconds faster than I, on average. I have never beaten him in those days.

A couple of years ago, we rowed a double at the Worlds Masters Regatta in Hazewinkel, and I also watched him race his Masters single. With much less training under his belt than I (and even less impressive erg scores), he managed to row a pretty decent time.

It seems that in a race situation, he is able to row closer to the true limits of his physiology than I. To endure more pain. It looks like he is tougher, but then why does he not show that in training?

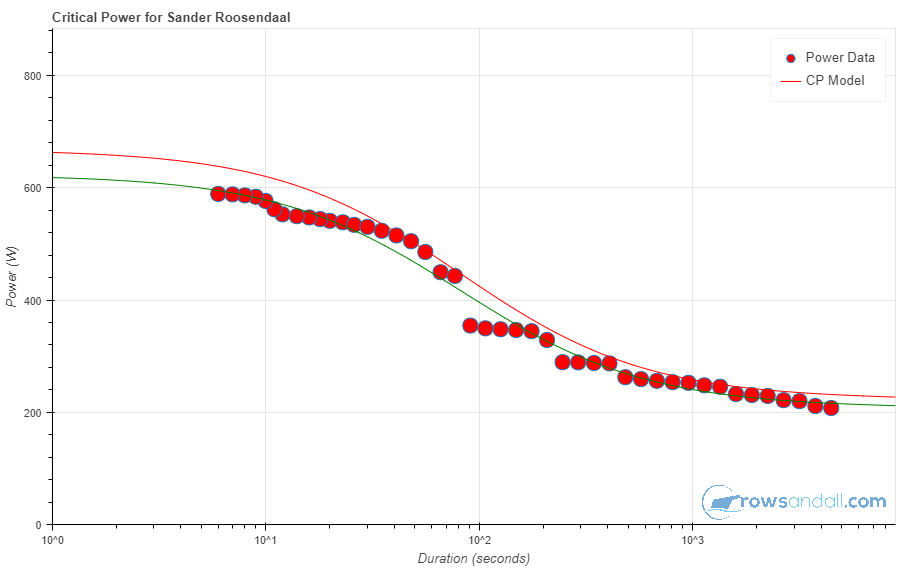

The Critical Power Chart

The chart below is my Critical Power chart, it shows how hard I can push (in Watts) for how long. Since I have started rowing with data, a lot of my thinking (and racing) involves looking at this chart.

But my friend Arjan would have difficulty constructing a reliable CP chart from his training data. For me, the knowledge from the CP chart is a good way to ensure smart pacing and avoiding the go-out-as-hard-as-you-can-and-hang-on-for-dear-life strategy that so often leads to disappointing results. On the other hand, though, I sometimes wonder if I am really rowing at my true limits.

We say that we are giving our maximum effort on a 2k test, but if a lion would enter the erg room 1 second after the finish of an erg test, I bet we would have the energy to run away as fast as we can. Clearly, most people look tired at the end of an erg test, but they do not die from exhaustion as a result.

When I started training for competetive rowing again as a Masters rower, I listened to a podcast about the “central governor” theory, and I was puzzled. According to Wikipedia:

The central governor is a proposed process in the brain that regulates exercise in regard to a neurally calculated safe exertion by the body. In particular, physical activity is controlled so that its intensity cannot threaten the body’s homeostasis by causing anoxic damage to the heart muscle. The central governor limits exercise by reducing the neural recruitment of muscle fibers. This reduced recruitment causes the sensation of fatigue.

On the one hand, this seems a plausible explanation, but it also posed the question. If this is true, is this central governor somehow trainable, or should I just be accepting that I work 30% under my true limit, and train just the same way as I used to, to at least make sure that my 70% effort is improving?

I find it hard to accept theories that one cannot disprove, or that do not have any impact on decisions I make.

This question is exactly the topic of the book by Alex Hutchinson. The book starts and ends with the attempt, on May 6, 2017, to run a marathon in under 2 hours. In the thirteen chapters that follow, he covers the current status of research on the interactions between mind and body in athletes, explorers, and ordinary people. Ending, after 267 very readable pages, with that same marathon record attempt.

Hutchinson is an entertaining writer. He describes the struggles of the various Antarctic expeditions and other situations were humans were forced to reach to their ultimate physiological limits. A lot of people die in these 267 pages. Some barely survive.

Hutchington also describes a large variety of experiments were people were tricked into performing beyond the limitations their mind set them, including workout room thermometers with false (lower) readings, isotonic sports drinks and placebos, and even sending electric current through parts of your brain. Fascinating stuff.

Hutchington also describes a large variety of experiments were people were tricked into performing beyond the limitations their mind set them, including workout room thermometers with false (lower) readings, isotonic sports drinks and placebos, and even sending electric current through parts of your brain. Fascinating stuff.

One of the strong findings that I am experiencing every week is that doing hard mental work before exercising leads to a performance drop. If only the training effect of rowing a steady state row at 180W at the end of the working week could be the same as rowing it at 200W on Monday!

Yes, people are zapping their brains to improve their athletic performance! Without knowing the long term effects of this, I personally would be extremely cautious. I would also consider it doping. At the same time it is weirdly fascinating to see websites like this one: tDCS Device Comparison.

When you finish reading this book, which I do recommend you do, you will have a good overview of the status of research in this area, and you will know that things are not as black and white as stated by the central governor theory. How these things work exactly, we don’t know. The scientific debate is still ongoing. But thinking about what it boils down for an ordinary masters rower, I think it is the following:

- Train according to established training principles to develop your endurance, strength and pain tolerance.

- It is important to explore how working at race pace feels. By exposing your body to the pain and finding out that you actually do survive it, you can be slightly more comfortable during a race, and thus reach a better performance.

- Focus and concentration exercises do help, as do race “routines”, and attention areas during the race (sit up, chest up, ten strokes on technique) that help you row through a painful part of the race. It also works to just focus on completing the current 500m interval, and not worry about the entire set.

Or, as the training haiku quoted in the book goes:

Run lots of miles

Some faster than your race pace

Rest once in a while

Also, while I do believe that it is good to do something crazy like rowing a 2k at a faster pace than suggested by your CP chart, the analytical, data-driven approach to training is probably the best way to fast improvements, finding out what works and what not, and getting “free speed”.